Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

The art of Joe Furlonger has been the happy backdrop of my life. Some of my fondest memories from childhood are of playing with his sons during school holidays under their house on the Pacific Highway at Palm Beach in Queensland. Wetsuits and canvases draped over surfaced, the smell of turpentine overpowered by that of the fresh herbs growing in great abundance in the sunny spot just outside the studio entrance. When we bored or it rained, we would draw for hours. Growing up in our warehouse apartment above the gallery I could never escape the mesmeric shapes of his monumental Fishermen, bright pink atop a lurid blue that my father donated to the Queensland Art Gallery just before he passed away. When I moved to the UK Furlonger prints hung in my Cambridge rooms or my flat in London. Our wedding present from my father to fill a wall in our tiny first house in was a large deep yellow Central Queensland landscape that had hung in our Hunter Valley farm that we sold to buy a shoebox in Paddington. When my father died young at 72, I made the decision to disperse an enormous collection that belonged to another man and which I could never keep together without it being a painful living monument. The only works in the estate of well over 2,000 pieces many of which were donated to institutions in QLD and NSW, were the paintings of Joe Furlonger. I felt part of their story. Many of the views I had seen with Furlonger having travelled with him as a boy with my adventurous father or as a young man as his dealer and sometime writer on his work.

I have known Joe my entire life, born the same year as his first exhibition with my father in Brisbane in 1985. He is more of a constant figure in my own forty years than any other including my parents. He is the only person I call to talk about exhibitions I want to see around the world or if I simply need a like mind to talk with to replace my late father when I miss his voice. When I learnt of Bill Robinson’s passing in August 2025, I texted Joe, a lifelong friend and protégé of that artist immediately. I gave a quote to the Heraldand searched out of his web presence to reminisce fondly about his works, my father’s art library having been gifted earlier in the year to the National Art School, Sydney. Whilst Robinson was a rare artist with a museum dedicated to a national treasure during his lifetime that institution supports a useful website as a central repository for information and some work. I thought for a moment of the various catalogue essays I have written about Joe throughout the years or the book on him I had started but have not yet finished and lamented that artists’ books, like much of the world they inhabited prior to the wildfire of social media overcame the landscape, were now a thing of the past. Whilst I would eventually get around to giving Joe the book he deserves, I wondered who would read it let alone have a bookshelf to put it on. After all, I had just given 60 tea chests of catalogues to an art school whose students were almost certainly going to open about 3% of them, ever.

My father and I fell out of love with the art market towards the end of his life. I declared that the art world had been overtaken by dickheads in the pages of The Art Newspaper when we closed our doors, but it has not taken long for the vacuousness of the internet to take out the dickheads, too. And yet art itself will not die, even if computers can make art now. A fellow collector and I were discussing this when I explained why I stepped away from two tentative attempts to reenter art dealing. I told him that computers canmake art, but only bad art. Which shouldn’t worry anyone because humans have been making bad art for years. But good artists will live forever. It is the same with writers and musicians. So I think human intelligence will prevail. It must, if culture is to survive.

And so, adaptation is a key element and that is what this project is about. An artist like Joe Furlonger will never evolve without the regular exhibition of new work. When an artist stops producing and presenting new forms or expressions, be they reworkings of old themes, renditions of familiar vistas or completely mad new shapes then they cease to make the case that their work retains meaning. However, commercial galleries that are run as businesses and not hobbies for the uber wealthy will die within a generation. There simply are not enough engaged people in their late 30s today who want to go and see a show. However, the volume of cashed up investment bankers and techies out there with wads of cash and zero knowledge or confidence in art is far, far higher than the 00s when the contemporary art market in Australia last boomed. Part of this issue is the arrogance and elitist attitudes of so many art dealers who instantly turn off the masters of the universe who would rather spend $400k on a numberplate for their $100k Range Rover than give a snotty dealer $14k for an incredible painting that will fill his life with some joy if not meaning. It has taken me some years of reflection out of the game to feel for the potential collectors in this country. They do live digital lives to destress and they are not philistines. They want to know about art but they invariably get burnt early and don’t go back.

I feel the next generation haven’t been taken on the journey nor have artists had the tools to build platforms to showcase their work. This educational part of the puzzle is not one that dealers are always capable of because many are quite reasonably focussed on margins and marketing. Who has the time to build and populate a website dedicated to one artist whose work they feel to be amongst the best made in the last century in this country? Well, I do and so I have started this.

One of the most prevalent comments about Furlonger I hear from museum curators, critics and significant private collectors is that he is underrated. I disagree because I don’t really know what that means in Australia. We have such a curious art market that rewards what is fashionable than what is inherently good, mainly because so few can appreciate what makes one line or mark better than another. This is the notion of having a good eye. It is a nonsense that you either have it or you don’t. It comes from constant curiosity and deep, regular looking at things and making honest judgments.

It is impossible to explain succinctly why I have such a passion for the work of Joe Furlonger. I could describe the feelings that run through your body when his seascapes, their many thin layers of acrylic bound pigment actually change colour and form as the light of the day changes and new things are revealed. But you’d need to be in my living room with a gin and tonic with me at the end of the day. Or you’d need your own. I could try and explain why I have not sold any of the 40 paintings of his I own despite the fact that even with three entire spaces in my soon to be finished new home dedicated only to his art. I have works on loan to others in Sydney and Brisbane, being enjoyed on walls, simply because I can’t bring myself to sell them.

This project is a notebook of sorts for myself, too. I will draw as much together as I can from the written material published over four decades and will attempt some new essays. But more than that it is, I hope a useful resource for his primary dealers and the hundreds of collectors who have bought his works, the museums that continue to collect, show and tour his exhibitions and hopefully a new generation of collectors who will emerge from a very different art buying experience than when one walked into a gallery on a wet Saturday and sat down for a chat and left with something they’d live with and love for the rest of their lives.

Evan Hughes, Sydney.

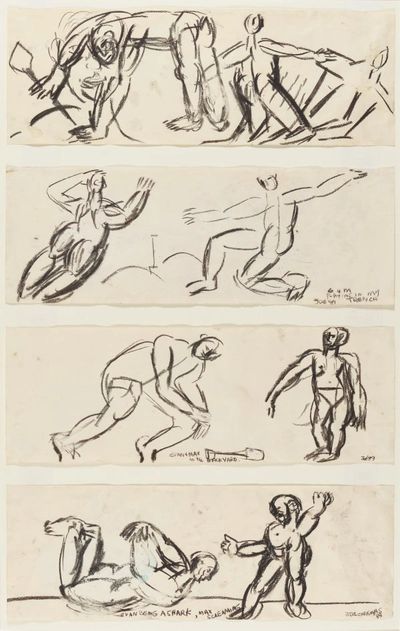

Evan being a shark, Max Screaming, 1989, pencil on paper. Art Gallery of NSW

Joe Furlonger mostly uses acrylic bound pigment on canvas. This website uses cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.